Appendix 8 - The Missing Knights and Men-at-arms

INTRODUCTION: The following discussion focuses on the possible identity of the most senior retinue personnel whose names are missing from the surviving record. As it would seem that it will never be possible to confirm the names of the men involved, it must be clearly stated here that the suggestions made are only speculative. They are, however, based on the same sort of circumstantial evidence which has been used to support the analysis of the details of the soldiers whose names are still visible on the remainder of the E101/45/17 roll. They are offered because they seem to reveal some interesting possibilities that support the basic proposal that the retinue was closely connected to the Beaufort family in the third decade of the fifteenth century.

This appendix deals with the men of the retinue shown in E101/45/17 m.1 who it has not been possible to include in the SLME database due to their names being illegible, as a result of the damage to the beginning of the muster roll. It seems that at least 21 men’s names have been obscured and this would bring the number of knights and men-at-arms to 100, which is a number very likely to have been indented for by a leader bringing the large retinue involved in this case. This suggestion is based on an examination of the roll showing that despite the damage done, each of these lines can be identified by the point confirming the man’s presence at the muster made by the scribe, still being visible.

It has also been proposed that the retinue could have been intended to comprise 120 men-at-arms and 360 archers but the captain had failed to recruit sufficient men-at-arms and raised 26 extra archers instead. This was certainly allowable under the terms of Salisbury’s own indenture with the Crown in 1428 and it seems likely that this flexibility would have been available to his sub-captains. This would mean that there were probably a further 9 men-at-arms, of the most senior ranks whose names were at the head of the muster roll, now completely lost due to the damage. These would include any dukes, earls, bannerets or knights listed in order of precedence.

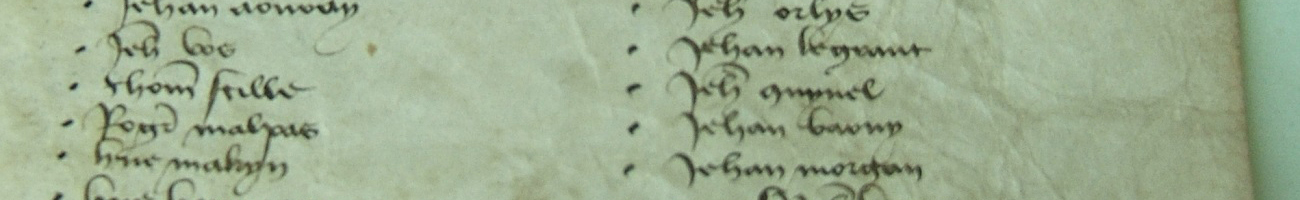

Mention has already been made of the attempt to decipher some of the remaining names by using an ultraviolet light on the membrane and this produced a group of 11 possibilities. These were from the section of the first membrane furthest from the worst deterioration i.e. lower down and nearest to the names that are still legible (the first of these being Thomas Swynford). These men would probably have been of lesser prestige, as men-at-arms, although likely to include esquires of knightly families.The details of one; a John Cropello have already been mentioned in the main text and this is helpful in establishing a link with the Swynfords. The remaining names are suggested to be as follows: John Henrison, Walter Smyth, Richard Glover, William Forfour, John Jacson, Robert Treveur, Henry Baroue, William Bell, Robert Nesbete and William Slege.

This is not a very promising list, including some very common surnames and none that can be said to be well-known among historical records. However, sometimes they can be traced even if with a modicum of doubt. A John Henrison appears on the Yorkshire feudal aids list in 1428 among a group of tenants which include members of the Pudsay family (one of whom is also listed as a man-at-arms on m.1 of the E101/45/17 roll.[1] A Richard Glover is found mentioned as a feoffee of Sir William Fraunk at his inquisition post mortem in Lincolnshire in 1432, along with John Cotom, who is listed on m.3 of the same roll and John Copeland who is shown on the SLME database as fighting in France in 1429.[2]

Robert Treveur may have been the Robert Travers of Legbourne, Lincs, who received a letter of protection in 1417, giving his captain as Sir Thomas Bowet.[3] Several Bowets campaigned with the Beauforts.There are three later instances of a Travers being led by a Beaufort on the SLME database, but there are also other similar names like ‘Trevor’ and ‘Treveneur’ also led by Beauforts or other Yorkshire captains in the late 1420s - 1440s. There are similar difficulties with the identification of Henry Baroue, whose name might also have been spelt ‘Barwe’, However, a John Barowe of Hatcliffe, Lincs, did take part in an inquisition post mortem for Margaret, widow of Stephen Le Scrope, in 1423.[4]

Robert Nesbete can only be linked to a family and village of the same name (Nesbit) on the Northumberland/Durham border where they built a castle in the twelfth century. William Slege may have been the William Slegh of Sawley who was juror at the inquisition post mortem of Hugh Wyloughby at Sawley, Derbyshire, in 1422.[5] There may also be a link with John Slegh, Chief Butler of England in the 1380-90s.[6] Neither of these men can be shown to have had any connection with the military campaigns of the period.

William Belle and Walter Smyth have such common names, it is not possible to offer any reliable suggestion on their origins.There was though a William Belle serving as an additional man-at-arms in the official retinue of Sir John Salvayn, bailli of Rouen, in 1429.[7] He may have been either the father or son of the same name who served with Thomas, duke of Exeter and Sir Hugh Lutterell at the Garrison of Harfleur in 1415-16 and 1418.[8]

In summary then, while there are some indications of military activity at around the right time and some links to the counties which the remainder of those mustered often come from and in which Beaufort property existed, these biographies add little that is helpful.

There remain the men whose names cannot be read at all, who would likely have been much more recognisable considering their prominent position on the muster roll. Is it possible to propose who any of these probably were? It would be necessary to examine who was known to have taken part in other campaigns in France and look for candidates who came from the major areas of recruitment as evidenced by the study of the men already identified from the rest of the muster list.Taking this approach, and concentrating on those men who can be shown to have campaigned shortly before and after 1428, the following individuals are proposed as men who might be expected to have responded to an expedition commanded by such a charismatic leader as Thomas, earl of Salisbury, and to be a part of a retinue led by a captain of royal blood.

The first men to be considered have already been mentioned as receiving letters of protection or attorney at the time the retinue was being recruited. Sir William Drury, Thomas Swynford’s brother-in-law since 1421 and a member of Thomas, duke of Exeter’s household in 1426 was not the first member of his family to follow a Beaufort to war. Roger Drury, a man-at-arms who had been part of the garrison at Harfleur in 1415-16 captained by Exeter, was probably William’s brother, named for his father Sir Roger, who lived at Rougham, Lincolnshire.[9]

Sir Roger was J.P. and three times m.p. for Suffolk as well as being a member of various commissions in the county. He was also part of the force led by Thomas of Woodstock and Henry Bolinbroke that defeated the earl of Oxford at Radcot Bridge in 1387 as part of the struggle for power led by ‘the appellants’.[10] This incurred the enmity of Richard II until the king’s deposition in 1399 but brought favour from Bolinbroke as Henry IV. Sir William Drury his heir, in marrying Catherine Swynford became related to the Beauforts and also the Crophills through her mother, Jane Crophill (Sir Thomas Swynford’s first wife). The Drury family as a whole had a long history of military service and this continued in the period 1429-31 and through to 1443 when a Nicholas Drury, archer, served in France with John Beaufort, duke of Somerset.[11]

Also already mentioned is Sir John Shardelow, another member of Exeter’s household. Shardelow was son and heir of Robert Shardelow, knight and took seizin of his father’s lands in Cambridge in 1423, having proved his age. His father had held this property as tenant in chief of the king.[12] He also had property in Norfolk and in 1424 is described as John Shardelowe, esquire, of Suffolk when he was recorded as one of three men providing mainprise of five hundred marks to John Graa knight, as a guarantee that he would keep the peace with his wife.[13] Shardelowe gave Edmund Beaufort, count of Mortain, as his captain in France in his letter of protection of 1427.[14] He had a letter of attorney in 1428.[15] He was dead by 1432, when his inquisition post mortem showed that he held for life the manor called ‘Shardelowes’ in Cowlinge, Suffolk’ of Sir William Drury. The Shardelows military service can be traced back to 1373.[16]

A third man obtaining a letter of protection in 1428 was Robert Cressener of Suffolk, possibly of Hawkendon.[17]There was a man of this name there who held a number of Manors in this county, Essex and Huntingdonshire, but he was dead by 1410.[18] His son and heir was a William, so it seems likely the soldier was a younger son or other relative. William was a ward of Sir Richard Waldegrave who owned lands close to the Cressoners in Suffolk. A Robert Cressener is named as a feoffee of Waldegrave ‘s manor of Edwardston (Suffolk) in the latter’s will, dated 22nd November 1424, together with a Walter Cressener.[19] Both are described as esquires. A Robert Cressener is also found offering military service again in 1436, when he is mentioned in a letter of protection as following Edward Beaufort, count of Mortain in France.[20] William Cressener had previously fought in 1415 and 1417 with the duke of Gloucester, a cousin of the Beauforts.[21] Although Robert Cressener gives the earl of Salisbury as his captain in 1428, no other previous links with the earl have been discovered.

Similarly Theobald Gorges, Knight, was granted a letter of protection in 1428[22] and in 1440 intended to be part of the retinue led by John Beaufort duke of Somerset,[23]where he gave himself as of Wraxall, Somerset. Gorges also served a number of other captains in a long career, including Sir Richard Hankford of Devon at the siege of Orleans in 1429.[24] According to Thomas, earl of Salisbury’s inquisition post mortem in 1429 the Hankford family had held two knights fees of Salisbury in Devon and Richard had also married the earl’s sister. It seems more probable then, that both Gorges and Hankford were part of Salisbury’s personal retinue. But, interestingly, Hankford was also captain to John Asteley ,man-at-arms, who had held five manors of Thomas Beaufort, duke of Exeter, according to the latter’s inquisition post mortem in 1427.[25] This property would have passed to John Beaufort by 1428 and it seems reasonable to suggest that Asterley was one of the E 101/45/17 retinue who cannot now be identified but who stayed on in France, joining Hankford’s retinue as a man-at-arms by early 1429. Asteley (Astellay) also served with Edward Beaufort at the Garrison of Gisors in 1430.[26]

For further candidates for the senior ranks of the retinue we can return to the applicants for letters of protection and ex-members of the duke of Exeter’s household. To begin with, a Sir John Curson is mentioned in Worcester’s itineraries as serving Exeter alongside others discussed here.[27] A John Curson knight, son of Sir John Curson (died in 1415), is mentioned in William Miller’s ‘Topographical History of Norfolk’ of 1805 as releasing various manors in Norfolk in 1414.[28] This seems to have been with a view to putting the estates into the hands of trustees prior to his embarkation for France in May 1415 as part of the retinue of Sir Thomas Erpingham who was the steward of the king’s household. The National Archives hold details of similar quitclaims in 1432-33.[29] This must be the same man concerned in a case of debt heard at the court of common pleas in 1449 where he is described as of Belaugh, Norfolk.[30] He died there in 1471.[31] He is last recorded as intending to serve in France in 1423.[32]

There is also a John Curson, man-at-arms, initially serving with John, Lord Grey of Codnor, in 1417 and 1421, and then getting letters of protection in 1425, 1426, and 1428.[33] He gives his home as Croxall, Derbyshire, and can also be proposed as another of the unidentified men in 1428. The biography of his father (also John) who died in 1405 is given in the History of Parliament.[34] It notes his probable descent from Sir Roger Curson of Kedelston in the same county and refers to a relationship with a Sir John Curson, one of John of Gaunt’s household knights who also had estates in Croxall. This is presumably the man based in Norfolk. John Curson esquire campaigned with Gaunt and later rose to become the steward of the duchy of Lancaster Lordship of Tutbury. He was also involved in property dealings with both Sir John and Lord Grey. He was a strong supporter of Henry Bolingbroke and raised an apparently large private force when in 1399 Bolingbroke returned to England to reclaim his inheritance and take the throne. Curson was subsequently appointed to the royal council, became Henry IV’s Treasurer of War and was heavily involved in military campaigns on the Scottish Borders.

John Curson junior was 12 years old at his father’s death, making him old enough to have fought with Grey and still be only 35 in 1428. He is mentioned as John Curson of Derbyshire (presumably Croxall) a creditor in a case of debt heard in Chancery in 1434 .[35] He is probably the John Curson, echeator for Notts and Derbyshire mentioned in the Escheators Files for November 1435-36 and 1440-41 and the Sheriff of Derbyshire and Notts in 1437.[36] He was dead by 1450.[37]

The only Curson family link with the Beauforts on the SLME database is a Hugh Curson, crossbowman, who was a member of the garrison at Harfleur in 1418,[38] but the mention of Sir John Curson as a further member of Thomas duke of Exeter’s household sometime before Beaufort’s death in 1426 gives his being part of a Beaufort retinue in 1428 some credibility.[39] In addition, he is also possibly mentioned as being a member of Exeter’s retinue again when he received a letter of protection in 1423 (although the exact meaning of the entry is unclear and the SLMEdatabase says no captain is given, it can be read as being a member of Exeter’s retinue in the original text).[40]

So both these men were militarily active in the years leading up to Salisbury’s last campaign and John Curson esquire did apply for a letter of protection in the year in question.[41]

Richard Cumberton (Comberton) is yet another man securing a letter of protection in 1428 and within two days of John Curson.[42] Inquisitions post mortem on William Comberton (a ward of the king) were held in Northants and Middlesex in June 1425, ( he himself being heir of James Northampton).[43] The lands concerned were held ‘of the king in chief ‘ and were a ninth part of a knight’s fee. Richard was confirmed as William’s brother and heir. He proved his age in August 1425, was said to have been born in Hoxton in Shoreditch, Middlesex and was 21 years old and more.[44] His own inquisition post mortem was held in Middlesex in June 1432.[45] Richard had property in Wellingborough, Northants and Tottenham in Middlesex and was owed a debt of £143:13:6 at his death so was of sufficient means to support himself as a man-at-arms. Cumberton had also obtained a letter of attorney in 1426 which is before Edmund Beaufort began his own military career but Thomas, earl of Salisbury, was on campaign, suggesting that it was he who recruited Cumberton in 1428.[46] However, there is no sign of Cumberton among his retinue in 1426, his indentees in 1427 or his tenants at his death.There is the reference to a Swynford being mustered with Salisbury in 1426 though[47] (see fn 54 in the main text). It could be that Thomas Swynford and Cumberton were both with Salisbury in that year and Cumberton then joined Thomas Swynford in Salisbury’s army as part of the Beaufort retinue in 1428.[48]

The next man for consideration is Sir Richard Carbonel who, like his father Sir John, was a member of Exeter’s household. Sir John of Sebton, in Norfolk, was also lord of Metton in the same county and was captained by Exeter in 1412, according to his letters of attorney and protection in that year.[49] He was dead by 1425 and was succeeded by his son Sir Richard, who held a knights fee in Norfolk from Exeter in 1427 as shown in the duke’s inquisition post mortem (part of the Wormegay estate).[50] He was a mainpernor for Exeter and received a special bequest in his will.[51] Richard obtained a letter of attorney in 1427 and was said by Worcester to have died in foreign parts on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1429, made possibly as thanks for his survival on campaign in the previous year.[52] An Inquisition post mortem in 1432 which dealt with lands he held in Suffolk contradicts this, giving his death as taking place on 30 July 1430.[53] He also held Caston Manor in Norfolk from the king in chief of the Honour of Wormegay as a knight’s fee in 1427.[54]

Another man serving as part of Exeter’s affinity was William Wolf, knight, of Hintlesham, Suffolk[55] . He is first found in 1415 as a man-at-arms fighting in France with Thomas FitzAlan, earl of Arundel.[56] Anne Curry mentions in her book ‘ A Soldier’s Chronicle of the Hundred Years War’ that Worcester also noted Wolfe as a one-time groom knight with Thomas, Duke of Clarence and she suggests that Wolfe was possibly knighted on the eve of the Battle of Bauge in 1421 or else in 1419 when the duke was in Paris.[57] Curry says he was in any case a knight by 1422 when he joined the expeditionary force going to France[58]. He is not found again as a soldier until 1429 when he entered into an indenture with the king, being retained to accompany him on the ‘Coronation” expedition to France of September 1429-30.[59] In 1430 he received a letter of attorney, presumably for the same campaign.[60]

Wolfe had in the meantime been appointed to various commissions in Suffolk in the mid 1420-30s. In 1434 Wolfe was ordered, along with Henry Drury, as knights of the shire, to identify those inhabitants of the county they thought necessary to take the oath not to maintain peacebreakers.[61] In 1436 he served on a commission of array with Sir William Drury his apparent companion in arms in 1428.[62] In the same year he was commissioned to ensure the safe conduct of victuals to Calais, commandeering shipping and recruiting fencible men and mariners from Norfolk and Suffolk to accompany them to the forces of the duke of Gloucester in France. [63]

Sir William had died by 1446 but other men named Wolf are found following Edmund and John Beaufort in 1430 and 1443 respectively (although it is a common name).[64] Given his involvement in France before and immediately afterwards, It would seem quite feasible that this man also took part in the campaign in 1428.

William Calthorp (esquire?) is recalled by a man surnamed Celere in William Worcester’s itineraries as another of the 140 horsemen Thomas, duke of Exeter, was said to maintain within his household, although he is not mentioned in Elder’s comprehensive listing of those involved in 1426.[65] This is possibly the William Celer, man-at-arms, mentioned on the SLME database as serving with Sir John Arundel and/or the William Seler, man-at-arms on campaign with Humphrey Stafford duke of Buckingham in 1421.[66] [67] According to the Topographical History of the County of Norfolk published by William Miller in 1807, a Sir William Calthorpe held the lordships of Calthorp, Seething, Burnham and Thorp in Norfolk.[68] His will was dated Dec 19 1420 and his grandson, another William, was his heir, his son having already died. William aged 11 was still a minor and became a ward of the king. An inquisition to prove William’s age was held in March 1431 when he was said to have been 21 in the previous month.[69] It seems likely then that William had joined the duke’s household in his minority and this is supported by William, his grandfather being shown as holding knights fees of Exeter in Fincham and Swanton, Norfolk at the duke’s death in 1426.

Calthorp would have been brought up then in the expectation of giving military service and knew well others from Exeter’s household who were to take part in the campaign in 1428, not least Thomas Swynford, who is found on the retinue detailed on the E101/45/17 m1. William was included in the list of men asked to swear an oath not to harbour any peacebreakers in 1434, which suggests a man used to the use of arms, although he was not knighted until 1458. Nor is there any evidence of his undertaking military service on the SLME database except a long history of family involvement. Even so, the balance of probabilities does seem to support his participation alongside other close associates at a critical point in the French war. If John Beaufort the new duke of Somerset was also hoping to lead a retinue personally, it would have provided a good opportunity of advancement for a young soldier.

There were three or four John Colvylle/Colville/Colviles who can be found on the SLME database serving in France in the first thirty years of the fifthteenth century and may have been involved in Salisbury’s campaign in 1428. The most notable (Sir John Colville born 1365 - died 1446) came from Carlton Colville, Suffolk but was also lord of manors in Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. Among these were a manor in Newton in Cambridge and three knights fees in Thorpland, Gayton and Wallingford in Norfolk. These last were held of Thomas Beaufort, duke of Exeter, according to the inquisition post-mortem on the latter’s property holdings in 1427.[70] He was a king's knight and employed on a number of diplomatic missions during a long career that also included several shrieval appointments and military service. He first went on campaign with the duke of Clarence in 1412 and formed a close relationship with the duke for the rest of the latter’s life.[71] He served with Clarence again in 1415, being found on the list of those noted as sick after the siege of Harfleur. Thereafter, there is no record of any military activity.[72] Michael Warner gives a very full biography of Colville’s colourful life in his book: ‘The Agincourt Campaign of 1415; The retinues of the Dukes of Clarence and Gloucester’, Woodbridge 2021.

In any case this man would have been 63 in 1428 and rather old to go on campaign and he was by then, heavily involved in county administration as well as raising a loan for the king in that year. In the following one, he was also appointed as justice of the Peace, so it seems uncertain whether this is the John Colville, knight who, obtained a letter of attorney for his visit to France in 1429.[73] But Warner also mentions that Sir John had a son, again a Sir John, probably born soon after1406. He apparently performed similar shrieval service to his father as well as military service. This John Colville married Ann Inglose, who was formerly the wife of Sir John Calthorpe.

The other two John Colvilles were both from Yorkshire. The first was of Dale, Ingleby Arncliffe in East Harlsey. He was born in December 1393 and in 1415 was found by inquisition to be heir of his grandfather. However, he unfortunately died at the siege of Harfleur in October 1418 aged 24, without any heirs of his own. He had married Isabel Tilliol[74] in the same year when she was only 12 years of age. Isabel was sued for her husband’s debts in 1423 but received a royal pardon for not appearing before the justices.[75] It seems, though, that by 1429 when she was called to court on another of her former husband’s debts, she had married yet another John Colvyle, lately of Normandby, Yorks, who was her first husband’s cousin.[76] Both husbands were mentioned in the legal suit, the earlier one being described as ‘knight’. The second husband was described as ‘esquire’.[77] Once again a royal pardon was issued for her non-appearance at the hearing. This suggests some recognition of royal service probably by the earlier husband. The second husband seems to have died by 1437.[78] He is probably the man-at-arms describing himself as ‘of Ingleby’ who serves in the Scottish Marches in 1423 and 1429, and possibly as part of the Garrison of Evreux crue in 1431.[79]

It is quite possible, then, that both Sir John Colvyle junior of Norfolk and John Colvyll esquire of Yorkshire took part in Salisbury’s expedition in 1428. That they were both active soldiers is confirmed by their letters of protection or administration showing their intention to serve in 1429.[80] Neither of them can be found serving elsewhere in 1428, the knight was bound for France in 1429 and owed service to the Beauforts and both of them were from counties of considerable recruitment to the retinue under study. In 1440 a Sir John Colvile obtained a letter of protection during service in France and gave his captain as Walter Cressener.[81] In1443 there was also a John Colvyle archer in France and captained by John Beaufort, duke of Somerset.[82]

Sir John Gra was the son of a Yorkshire merchant born in 1384.[83] His father Thomas Graa York MP, married the heiress of Sir John Multon of Frampton which brought him control of a number of manors in Lincolnshire including Multon Hall and North Ingleby.[84] By 1411 Gra junior had married Margaret the daughter of Sir Roger Swillington of Swillington in Yorkshire and enjoyed an income of over £320 a year. She died in 1429 and left him a life interest in manors in Notts and Derbyshire, but he was unable to access these as a result of legal disputes and due to the cost of his prolonged military service in France, became heavily endebted. He is first found as part of the Garrison at Harfleur in 1415-16, already a knight and captained by Thomas, then earl of Dorset.[85] This suggests he was at the siege of the town. He continued in France in 1417 and received letters of protection or attorney for the same in 1417, 1419, 1421 and 1430.[86] Thereafter, there is no trace of military activity although his presence in France in the last year does support his possible involvement in Salisbury’s campaign. Gra gave himself as “of Ingleby’ on his letters of protection in 1417 and 1430, and as ‘alias John Gra of Swillington’ elsewhere in 1430.[87] He was also on the Yorkshire feudal aids list in 1428 described as ‘miles’.[88] This indicates that he held some of his land in that county from the king in chief. He also held his manors in Notts and Derby which his wife had inherited in the same way.

John Gra was plaintiff versus John Haket and other feoffes for the manor of Multon Hall in Lincs in 1427-28 so likely in England at that time.[89] Yet it is interesting that in December 1427 John Gra paid 20/- in the hanaper to defer his doing homage to the king for being given livery of these latter estates until the feast of the Purification of the Virgin Mary (February 1428).[90] This implies that he was not available personally until then and may relate to his being abroad on military service.

One indication of a relationship between Gra and the Beauforts is, however, provided much later in 1448. Here, a memorandum of acknowledgement refers to Graa granting all his lands in Saltfleteby and Somercotes, Lincs, to a group of men on condition they will return them to the grantor or his heirs when required or to perform his last will.[91]Such an arrangement was not uncommon but shows the utmost trust in the men involved. Given the nature of Gra’s career it is likely that these men were drawn from those who had been on campaign with him perhaps more than once. This seems to be the case and the group comprises some very prestigious names, which in itself shows that Graa was held in high esteem. It begins with John Mowbrey, earl marshall and continues with lords and knights who were present at several of the events in Gra’s own career between 1415 and 1430. Significantly they include “Thomas Swynford knight and Thomas Swynford his son”. It is dated Ingleby 17th April 2 Henry VI.[92] Graa is also found as a witness to the transfer of Sir Thomas’ manor of Kettlethorpe on 20th June 1429.[93]

Gra was still alive in 1456.[94] Despite his close connections to the Beauforts and Swynfords, his presence on the campaign in France in 1428 must remain in doubt, given that he had received letters of protection in previous years and might be expected to have sought another in view of his continued legal battle regarding his lands with Sir Thomas Cromwell.

The Hiltons

The Hiltons became established in Lincolnshire in the fifteenth century, Sir Godfrey Hilton having married Hawise, the daughter of Sir Andrew Luttrel, by 1419. Sir Godfrey was the younger son of Sir Robert Hilton of Swine and Winestead, Yorkshire. Hawise brought him the manors of Irnham and Corby in Lincolnshire, Gamston and Bridgford, Nottinghamshire and Hooton Pagnell, Yorkshire. In 1431, on the death of his brother Robert, he also inherited a life interest in the manor of Swine.[95]

Sir Godfrey apparently made good connections in Lincolnshire during the earlier part of his life and was made sheriff in 1421. He was involved early in the war in France being said to have taken part in the Agincourt campaign (although there is no evidence of this on the SLME database).[96] Thereafter, he returned to France to campaign in numerous years up to 1434.

Sir Godfrey Hilton certainly indented to serve the king in France from September 1424 to August !425.[97] He was his own captain at the Garrison of Louviers in that year[98] and probably in 1425, when he was given further letters of protection and attorney and led a retinue of 66 men.[99]

It may have been that Godfrey’s brother Robert was the man listed as serving as a man-at-arms in the E101/45/17 retinue although there were many men of that surname in France in the 1420s. Godfrey had had a son Godfrey by 1422.[100] Godfrey junior was described as an esquire when he was plaintiff in the Court of Chancery against his father for the detention of deeds in respect of the property inherited from his mother (dated 1422-1459).[101] Hawise had held much of her lands of the king in chief by knights fee. Godfrey senior planned to serve in France again in 1434 and was still alive in 1436 when he gave a recognisance of 200L to be levied in Lincolnshire.[102]

A Geoffrey Hilton, knight,obtained letters of protection and attorney for military service in 1418 captained by Thomas Beaufort duke of Exeter but in 1421 gave his captain as Sir Godfrey.[103] [104] Geoffrey Hilton then fought with Exeter in 1423.[105] A Geoffrey Hilton knight to William Cheyne, chief justice of the kings bench gave recognisance of 10L to be levied in Yorkshire on October 25th 1426.[106] He is recorded as intending to undertake military service for the last time in 1433 as Geoffrey Hylton of Wassand in the East Riding of Yorkshire.[107]

Other possible long-term family connections are a John de Hylton, archer who had been a member of the garrison at Harfleur in 1418 under Thomas Beaufort, by then duke of Exeter.[108] A Richard Hylton, man-at-arms, and a Thimstard Hylton, archer, who were part of Thomas Beaufort count of Perche’s retinue providing field service at the siege of Louviers in 1431.[109] A Godfrey Hylton man-at-arms (possibly the son of Sir Godfrey) and a Geoffrey Hylton archer were two of four Hyltons captained by John Beaufort duke of Somerset on his expedition to France in 1443.[110]

It should also be noted that the Luttrells were also regular participants in the expeditions in France. Sir Hugh Luterell was Thomas Beaufort’s lieutenant at Harfleur garrison in 1415 -16 and five of the family were among the duke of Exeter’s men in 1418.[111] Hawise was the heir of her brother Geoffrey Luterell, knight and she and her husband had to sue the abbot of Croxton for the return of a box of muniments left with him by Geoffrey Luterell ‘before his passage to Normandy on the king’s service”.[112] A further Chancery Court suit gave Godfrey Hilton as plaintiff and ‘esquire of the retinue of the duke of Exeter, husband of Hawise, sister and heiress of Geoffrey Lutterell Knight who fell at the siege of Rouen’.[113] The siege began in July 1418 and ended in January 1419 and Exeter took an active part in it. So we can establish that Godfrey Hilton and Geoffrey Lutterell were almost certainly on the same campaign and it is quite likely that the two families joined the same campaigns and fought in the same retinues when they could. What is not clear is the relationship between the older Godfrey and Geoffrey Hilton. However it seems that as the younger Godfrey was captained by a Beaufort in 1443, it is quite probable that if Edmund Beaufort led a retinue in 1428, at least one of the Hiltons would have been part of it.

John Bernard

This man’s letter of protection is recorded on the 12 May,1428 on the same membrane as John Beaufort, third earl of Somerset, Sir William Drury, Thomas Swynford and Thomas Borowe of Lynn in Norfolk. Like Drury, his captain is shown as John, Duke of Bedford, and Borowe gives Thomas Montague, earl of Salisbury as his. Yet this grouping may suggest that Bernard was in fact intended as part of Somerset’s retinue, and as was often the practice then, all five names had been submitted together on behalf of the captain, in this case Somerset, whose name heads the list. Certainly they came from the same part of the country.[114]

John Bernard seems to have been the son of John Bernard of Akenham, near Ipswich, Suffolk who was elected to parliament in 1397, 1407 and 1411. He had also been coroner and justice of the peace on occasions and searcher of ships and controller of customs and subsidies. He died in 1421 and made a provision in his will of 5L to be divided between those who had lost property in Normandy during the French wars.[115] Houghton assumes that it was his son John who was returned to parliament for Ipswich in 1423.

John Bernard senior gave Thomas Beaufort, earl of Somerset, as his captain in his letter of protection in 1402.[116]Later in 1415 a William Barnard, man-at-arms, joined Thomas Beaufort in the garrison at Harfleur.[117] John Bernard esquire was captained by William Phelip in the same year and again in 1417.[118] Phelip came from Dennington in Suffolk. Woodger, in his biography mentions how close were Phelip’s connections with Thomas Beaufort, from early in his career and who made him a trustee of his estates and executor of his will before his death late in 1426.[119]Beaufort held extensive property in Norfolk when he was granted by the king the Honour of Wormegay estate, formerly held by Lord Bardolph. Phelip was to marry one of Bardolph’s daughters and gradually acquired the estate himself after Beaufort’s death. He remained closely involved in the Beaufort estate affairs until his own death. So, the recruitment of men from the county to a Beaufort retinue in 1428 and the involvement of a former follower of Phelip is quite likely. Bernard junior seems to have been knighted between April 1429 and June 1430.

Other Bernards are shown on the SLME database including one entry, again for William Bernard, man-at-arms, part of a detachment from the garrison of Caen at the siege of Harfleur in September 1440, led by Edmund Beaufort.[120] A John Bernard was also militarily active in France in 1440 and 1441.[121] It was John Bernard junior who married Ellen Malory and held the manor of Welton in West Lindsey, Lincolnshire, in April 1429.[122]

CONCLUSION

A case of varying strength can be made for many of the men detailed here to have been one of the leading members of E101/45/17 retinue. To begin with, they were alive and of suitable age to fight in 1428. A number of them are on the feudal aids lists in the first quarter or so of the fifteenth century in the same Hundred or Wapentake, particularly in Norfolk and Suffolk, and so presumably were part of a local geographical network with shared values, military experience and civil responsibilities. They knew each other and were probably mutually supportive.[123] Drury, Shardelow, Cressener, John Curson esquire and Richard Cumberton all had close links with the duke of Exeter, and took letters of protection or attorney in 1428. Others, like John Curson, Carbonnel and Wolfe, knights, Calthorpe, Colvylle, Gra, the Hiltons and Asterley, had the same credentials for membership of the Beaufort retinue, only lacking a letter of protection or attorney, quite possibly because it was thought unnecessary. As tenants of royal lands, they would all have owed service to the Crown and might have been expected to join a retinue led by a man of royal blood.[124]

If more evidence of these men’s connection with the retinue were required it would seem best to seek links with the rest of the retinue. However, this proves largely inconclusive as so little can be discovered of the men proposed as being next on the retinue list (having examined the roll with an ultra-violet light) until we find Thomas Swynford, who does show some clear connections. Only John Henrison is found on the Yorks feudal aids list in 1428 and might have shown some joint activity with John Gra or John Colvyle, but this is not the case. The names given on the list below Thomas Swynford’s are equally unhelpful. It may be that this is because the men-at-arms concerned were part of the captain’s personal bodyguard/household and would not be connected in any significant way to the men of status who headed the retinue list. Alternatively, they may just have been a group of professional soldiers recruited at random by Edmund Beaufort in his brother, the earl’s absence due to his captivity in France since 1421.

It seems then, that we will have to accept that on the evidence available, this group of men are the most likely to have helped lead the retinue in 1428. Like the rest of the rank and file men involved they originated predominantly from Lincolnshire, East Anglia and Yorkshire. Most importantly they were men bred to military service with a well established connection to the Beaufort family’s own soldierly activity over many years. They would have been part of what promised to be a famous campaign led by the most illustrious commander of the day in the earl of Salisbury, while in many cases fulfilling a family commitment that went back to the time of John of Gaunt.

From the information we have, Wolf, Graa and the Hiltons would have been the most experienced campaigners, having served at least three times previously. They may have joined the same expedition in 1421 and Wolf and Graa might also have fought together in 1419. However, only Geoffrey Hilton, Shardelow, John Curson esquire and the young Richard Carbonel can be found on expedition in France in the previous three years. Again, this might reflect the difficulty Edward Beaufort probably had in attracting seasoned men to the family banner in the absence of his brother the earl.

Note:

It is, perhaps, in any case necessary to remind the reader that the possible presence of these men as senior members of this retinue is purely speculative. Further research may show them to be in France at this time but carrying out other duties or holding offices which would make it unlikely or even impossible to have taken part in Salisbury’s campaign. Likewise, any activity in England or elsewhere. Every effort has been taken, however, to identify whether this is the case without success.

THE END

[1]‘Inquisitions and assessments relating to feudal aids; with other analogous documents preserved in the Public Record Office AD 1283-1431’(Feudal Aids List), volume 6, 1920, p.274. (‘ Henryson)’.

[2] Mapping the Medieval Countryside, (MMC) website, Chancery Inquisitions Post Mortems, series 1’ Henry IV, 01/09/1422- 31/8/1433, C139/57/2.

[3] C76/100, m. 23.

[4] ‘MMC’, E-CIPM 114.

[5] ‘MMC’, E-CIPM 950.

[6] L.F.Woodger, ‘Scarburgh, John of Yorks’, HoP’ <www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/memberscarburgh-john-1415>,[Accessed 15 November 2022].

[7] SLME, AN, K63/7/18

[8] SLME, TNA, E101/47/39; E101/45/19.

[9] L.F.Woodger, ‘ Dury, Sir Roger of Thurston and Rougham, Suffolk, HoP <www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/memberdrury-roger-sir>1415>,[Accessed 15 November 2022].

[10] Ibid.

[11] SLME, E101/54/5 m.12.

[12] CR, 1422-29, p.12.

[13] CR, 1422-29, p.189. It is interesting that Robert Olyver, another of these men (or a namesake) appears as an archer in 1415-16 at the garrison of Harfleur under the command of Thomas Beaufort and similarly at the garrison of Rouen in 1422 before two further periods of service in France in 1430 and 1431, the latter at the siege of Louviers). SLME, TNA, E101/47/39; E11/50/22; C76/104 m,1; E101/52/10. A John Olyver served with John Beaufort in 1443; SLME, E101/54/5, m.12.

[14] C76/109, m.15.

[15] C76/110,m.4.

[16] C76/56, m.20.

[17] C76/110, m.6.

[18] MMC, CIPM 19-841. His lands in Preston and Netherhall in Otterly in Suffolk were held ‘of the’ duchy of Lancaster. C138/82/33 mm.5-6.

[19] CR, 1422-1429, p.125.

[20] C76/118, m.15.

[21] SLME, BL, Harley 782, f73v; E101/51/2, m.1.

[22] C76/110, m.5.

[23] C76/122, m.16.

[24] SLME, BNF. Fr.25768 no 339.

[25] MMC,E-CIPM, 22-799. This was in Snitterley, Glandford, Wiverton, Irmingland and Langham in Norfolk.

[26] SLME, ADE,11F 4069U.

[27] ‘Itineraries of William Worcester, edited from the unique MS, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge’ , ed. J. Harvey, Oxford 1969.

[28] ‘Victoria County History (VCH) of Norfolk’ vol.1pp.360-368, from W. Miller’s Topographical History of Norfolk, 1805; Letter of protection, SLME, TNA, C76/98 m.15.

[29] TNA, LR14/102.

[30] TNA, CP40/753.

[31] Miller, VCH, Norfolk, vol.1, pp. 360-368.

[32] C76/106, m.16.

[33] SLME, E101/51/2, m.18; E101/50/1, m.4; C76/107, m.8; C76/109, m.18; C76/110, m.5.

[34] C. Rawcliffe,’Curson-John’, HoP <www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/Curson-John-1405> [Accessed 15 November 2022].

[35] C131/229/35; E153/1436; E131/239/3.

[36] E13/2455; E153/1436; C131/230/3.

[37] CR, Hen. VI, p.108-109. A bond issued by his ‘late wife’ on June 5th, 28 Hen. VI.

[38] SLME, E101/48/6.

[39] J. H. Harvey. (Worcester), 1969.

[40] SLME, C76/106, m.16.

[41] SLME, C76/110, m.5 (Cursoun).

[42] SLME, C76/110, m.12.

[43] SLME, C139/14/7, mm.1-2.

[44] SLME, C139/20/49, mm. 1-2.

[45] SLME, C139/53/2, mm.1-2.

[46] SLME, C76/108, m.8; C76/108, m.12.

[47] SLME, BL, Add. Ch 94.

[48] SLME, C76/110, m.8.

[49] SLME, C76/95, m.8.

[50] MMC, E-CIPM, 22-799. This was in Caston, Toftrees, Beckerton, Shipdam, and Old Buckenham.

[51] A.J.Elder, The Beauforts, Appendix 3, p.204.

[52] C76/110; W.A. Copynger ‘ The Manors of Suffolk’, some notes on their history and devolution, with some pictures of the old manor houses’, vol. 4. The Hundred of Hoxne, 1905, p. 6. However the inquisition virtute officii held on the 4th October 1432 states that he died on 30 July 1430; E-CIPM 24-135; TNA E149/147/6 m.3.

[53] MMC, E-CIPM 23-623; C139/53/11.

[54] MMC, E-CIPM; C139/48/23 mm1-2.

[55] Worcester*; Inquisition post mortem of Katherine, late wife of William Wolfe in 1446, no. 421.

[56] SLME, E101/47, m1; C76/112, m,12.

[57] A.E. Curry and Remy Ambhul ‘A Soldier’s Chronicle of the Hundred Year’s War’ 2022, p.303, fn. 560.’

[58] Ibid, E403/655, m.1. Dan Spencer mentions that Sir William Wolf was made responsible for organizing a team of workers to construct a palace for King Henry V in Rouen in 1421-22. This confirms Wolf’s rank and presence in France that year. Journal of Medieval Military History, vol. XIII, ed. J. France, C.i. Rogers and K Devries, 2015, p.187, fn. 49; E364/69 m.7.

[59] Curry and Ambhul,TNA, E101/70/4/659.

[60] SLME, C76/112, m.12.

[61] CR, Hen VI, vol.2, p. 271.

[62] CPR, 1429-1436, Hen. VI, vol.2, p. 523.

[63] Ibid, p.536.

[64] SLME, BNF, MS Fr,25769 no 497; SLME, E101/54/5 m,13.

[65] Worcester; A. J. Elder.The Beauforts, Appendix 3, p.187.

[66] SLME, E101/44/30 no5 no5 m.1 dated as ‘Temp Hen V’.

[67] SLME, E101/50/1, m.4.

[68] Miller, Norfolk, pp. 513-521.

[69] MMC E-CIPM 23-592; C139/52/66.

[70] MMC, E-CIPM, 22-799, C139/30/56 mm13, 15; E-CIPM 22-800, E149/137/6, m.7.

[71] SLME, C76/95, m.12.

[72] M. P. Warner, pp. 93-94, fn 123.

[73] SLME, C76/95, m.12.

[74] CIPM, vol. 20: 1413-1420, no.370.

[75] CPR, 40/674, rot. 464d.

[76] J.M. Watson. ‘Genealogical Rambling’ (Watson) (online) August 23, 2014.

[77] Ibid; CPR, Hen. VI vol 1. P. 516.

[78] Watson; ibid.

[79] LSME, C71/83, m.13; C71/85, m.15; BL, Add. Ch. 180.

[80] LSME, C76/111, m.4; C71/85, m.15.

[81] LSME, C76/12,2 m.21.

[82] LSME, E101/54, m.10.

[83] Sometimes ‘Graa’.

[84] J.M. Mackman, ‘The Lincolnshire Gentry and the War of the Roses’ (The Lincolnshire Gentry). York, D.Phil.2000.

[85] LSME, E101/47/39.

[86] LSME, C76/100, m.22; C64/11, m.80; C76/10,3 m.8; C76/112, m.15.

[87] LSME, C76/100, m.22; C76/11, m.15;

[88] Feudal Aids List, vol. 6, 1920.

[89] Court of Chancery, C1/11/441.

[90] CR, Hen. VI: vol. 1 (1422-1429).

[91] CR, Hen. VI, vol.5, (1447-1448).

[92] This is a puzzle though as the date in the heading of the calendar item (1448) does not match the entry - the second year of Henry Vi’s reign was 1424. The date could be an error for the 26th year. That a Sir Thomas Swynford witnessed the document in that year is more difficult to explain. The original Sir Thomas had died in 1436 and his son, sir Thomas Swynford II ‘of Snaith’ had died in 1440 (see Alison Weir, ‘Katherine Swynson’, pp. 316-317). So in 1448 neither Thomas Swynford I or Thomas Swynford II could have acted as witness.They could have done though before the younger man’s knighthood by May 1431 or possibly December 1429.

Looking at the men who were granted the property it can be seen that one of them, Sir Lewis Robessart lived from 1390-1430. This supports the likelihood of the grant being made in 1424 and the item being put into the wrong calendar year. It also suggests that Gra was a friend of the Swynfords before the younger one went on his first campaign in 1427).

[93] Oxford University Research Archive: Charter Roll for Kettlethorpe.

[94] J.S. Mackman, ‘The Lincolnshire Gentry’; CR. Hen. VI: vol. 1 (1422-29).

[95] Mackman, p.309.

[96] C. Rawcliffe, ‘Hilton, Sir Godfrey’, HoP<www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/hilton-godfrey-sir-1459 >[Accessed 15 November 2022].

[97] SLME, E101/71/2/818.

[98] SLME, BNS, MS. Fr. 25767. No 64.

[99] SLME, C76/107, m.5; C76/107,m.3.

[100] MMC, E-CIPM, IPM of Hawise Hilton, C138/63/25B, mm1-2.

[101] C1/71/126.

[102] CR, Hen.VI: vol. 3 (1435-1441), pp. 46-50.

[103] SLME, C76/101, m.9.

[104] SLME,E101/50,m.4d.

[105] SLME, TNA, C76/106, m.16.

[106] CR. Hen. VI: vol. 1 (1422-1, p. 429).

[107] SLME, TNA, C76/115, m.8.

[108] SLME, TNA, E101/48/6.

[109] SLME, MS. Fr. 22688. No 197.

[110] SLME, TNA, E101/54/5, m.2; E101/54/5 m.8.

[111] SLME, TNA, E101/48/19; E101/48/6.

[112] C1/4/46 (1419-1422).

[113] C1/5/207.

[114] Thomas Swynford esquire (of the county of Lincoln) mainpernored John Bernard and John Swynerton on November 14 1425. Calendar of Fine Rolls, Henry VI, vol 15, p.116.

[115] K.N. Houghton, ‘Bernard, John III of Akenham, Suffolk’ HoP <www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/bernard-john1421-> [Accessed 15 November 2022].

[116] SLME, C76/87, m.27.

[117] SLME, E101/47/39. There is a record of a John Bernard, servant of the king’s household granting title deeds to a William Bernard, servant of the queen’s household in 1416, BHO, Reading Record Office, R/AT1/137.

[118] SLME, E101/45/m.2, E101/51/2, m.29.E101/46/16, m.1. A Wm Bernard of Akernam is mentioned in

A. Davidson, biography of Philip Bernard, Philip History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558<www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1509-1558/member/bernard-phelip-1538> [Accessed 15 November 2022].

[119] L.F.Woodger, ‘Sir William Phelip of Dennington, Suffolk’ HoP <www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/phelip-william-sir-145

1> [Accessed 15 November 2022].

[120] SLME, BNF, MS. Clairambault 220, no. 28.

[121] SLME, AN, K 66/1/62. BNF, MS. FR. 25776, no.1516.

[122] E40/7611.

[123] Helen Castor in her book “The King, The Crown and the Duchy of Lancaster: Public Authority and Private Power, 1399-1461’, Oxford 2000, pp68-74, gives a useful resume of the prominence of Thomas Beaufort in Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk in the reigns of Henry IV and Henry V. His increasingly close relationship with Sir Thomas Erpingham in the administration of local affairs coincided with Erpingham’s nephew, William Phillip entering Beaufort’s service as part of his household. Castor remarks that the notes made by William Worcerster of members of the household, testify to the influence of Beaufort’s lordship in both Norfolk and Suffolk. Of 22 names mentioned, the majority were knights and esquires of East Anglia and 6 of them are suggested here as members of the retinue under study.

[124] It is worth noting that in the first eleven years of the fifteenth century the Cabonnells, Colvyles, Hiltons and Swillingtons (Gra’s father -in-law) were all represented in the royal household as king’s knights together with Thomas Swynford as a knight of the chamber. See ‘The Royal Household and King’s Affinity 1360-1413’ in Service, Politics and Finance in England, 1986. C.Given-Wilson, appendix VI pp. 286-290.